We moor Albert just south of Blisworth Tunnel and often go through both

Blisworth and

Braunston Tunnels. As result we consider ourselves to be relatively experienced tunnel travellers. It was therefore interesting to see Andrew Denny's (

Granny Buttons) recent photos of

Preston Brook Tunnel because I've yet to take a decent photo anywhere in a tunnel, let alone one of an

air-shaft.

I then got thinking about a subject that occasionally vexes me, that's

tunnel lights. However, before I discuss them, I must repeat the old boating joke about tunnels. Sorry if you've heard it before.

What's the boater's definition of a pessimist? - someone who thinks the light at the end of the tunnel is a boat coming the other way.So what about tunnel lights? There are numerous different lights used on canal boats from humble automotive fog lights to gleaming brass fire-engine searchlights. So just what is the ideal light?

When we started boating I remember discovering some BW advice that a tunnel light should mainly illuminate the arch of the tunnel to aid steering and definitely NOT shine down the tunnel and blind boaters travelling in the other direction. At that time our boat carried a

Hella fog light fitted with a diffuse glass front lens, so I was happy.

After 12 years that advice still appears to me to be sound. After all boats only travel slowly through tunnels - steerers do not need to see hundreds of yards down the tunnel to avoid a boat coming in the other direction - it just doesn't help. However, appearances can be deceptive since some large searchlights are modified and use diffusers so they don't create problems and some small lights can produce narrow bright beams. It is the bright pencil thin beams that shine well down the tunnel that cause problems. They don't help the steerer of the boat on which they are mounted because they can't see the tunnel profile properly, and they definitely don't help those coming the other way!

So what sort of light does Albert have? Well it's not a searchlight but it is fairly large and is, of course, brass. According to Albert's the previous owner, the tunnel light was acquired as a pair by the owner of NB Oak who was friend and moored in the next berth at Bradford-on-Avon. He purchased a pair of

Lucas headlights at a classic car auction, kept one himself and gave the other to Mike Hurd for use on Albert.

Albert's Tunnel Light

Albert's Tunnel LightSo what model are the lights and what vehicle were they mounted on?

From an old catalogue I found that the lamp(s) are Lucas R160S circa 1932. It is a “King of the Road” Bi-flex lamp. It was probably originally chromed and is missing its reflector retaining clips. Crucially, it has a new front glass – possibly similar to Lucas “Difusa” glass. As a result it produces a diffuse beam of light. The R160S model was superseded by the LBD165S which has the same dimensions. It was fitted to the following 1932 cars: Armstrong Siddeley 20 h.p., Humber 16/50, and Morris Oxford 6 cyl. “LA”.

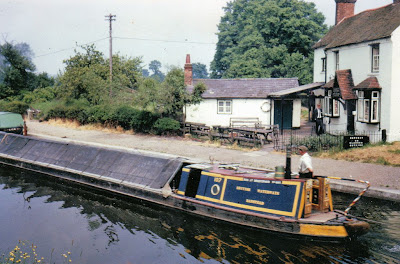

Morris Oxford with Lucas Bi-flex Headlamps

Morris Oxford with Lucas Bi-flex Headlamps

(crossing a canal bridge?)So does it matter where lights are mounted? Not in my view although it helps to avoid places where the crew can walk in front of the beam at crucial moments. The main thing is where they are pointed. Preferably not directly pointing at the roof of the tunnel or to the water (we've seen both of these). And certainly not moved around by the crew as we discovered last summer in Blisworth tunnel.

Happy tunnelling!

Steve Parkin